These eleven-year-olds, two boys, two girls, will talk about life. They are beyond precocious. They have read the great books. They have perfect memories. They feel and they think and they express themselves. They have families that tell life stories. All thoughts and experiences are mixed up together. They will narrate anyone’s story as a story of life. They will spare us the commentary—that old expression—and just tell it. They are pre-adolescent, so they do their best with strictly-speaking adult matters. They are preparing to take over the world. They have a different sort of vision, a different take on things. When you finish theology school, you are left with only one question: Why is there evil in the world? If good plays off of evil and it is the defining dynamic of the universe, then bad—evil—is also good.

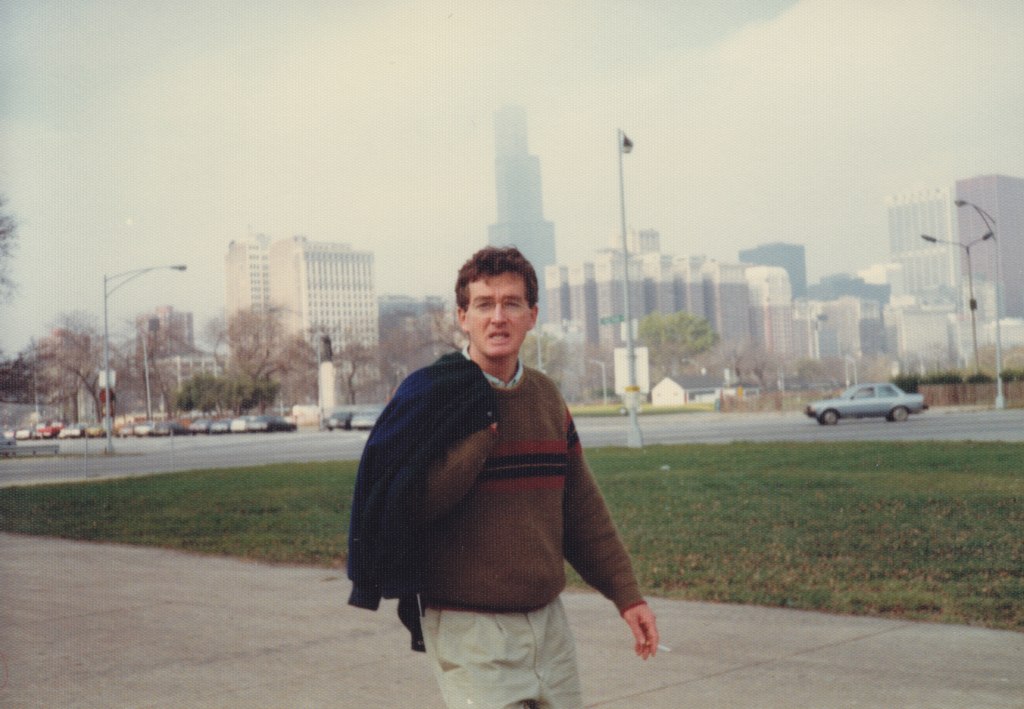

They don’t buy that. We—they—have acquired the wisdom of the ages, and now they shall acquire the ages. We have learned, and we will be good. They may pick a story their aunt or uncle told them, or a thought or observation they had while playing tiddlywinks on the veranda. It does not matter. Here is an example. Everything is connected to the universal story. Do you see this picture?

Here is how they will treat it. He is the gay uncle of one of them. He is good at telling life stories. He has a breadth of experience beyond your imagining. The voice goes to I—I did this and that; I went there, and I thought about that.

Let’s start. Do you see that sweater? I bought it in the top floor of a department store in Tokyo. Four of us were barging through, looking at stuff. My lover and two of his friends. They had been classmates at a trade school in Nagoya, and now they were adults, and still tight. They, as a group, stopped at this sweater on display on a shelf. My lover thought it was just right for me, and the other two concurred. They were taken with the idea of my owning it and wearing it. I thought, how can you stand two aisles from me and decide I ought to buy a piece of clothing? I am my own person; you can’t dress me. I am my own person. You can’t dress me.

Two months later, I was on a street in Chiba City. I seldom went to Chiba City, though I lived in Chiba Prefecture, and you would think there would be a logical connection. I experienced this observation two different times. There is a McDonald’s restaurant, and, separated by about five small businesses, there is another McDonald’s restaurant—on the same street. Here is the connection. I wore that sweater one of the times I walked by these two McDonald restaurants close together. I thought something like this: Here I am wearing this sweater, and there are two McDonald’s rather close together on the same street. The synapses that connected in my brain were: The edge of decision-making, corporate and personal. Why would McDonald’s do that?—I don’t hate this sweater. I will always remember the two food joints and wearing that sweater my friends told me to buy on the top floor of a department store in Tokyo.

That is how this story will be told, largely in the narrative voices of a group of fourteen-year-olds.